In 2023, I had the honor of hearing poet and priest,

, speak on the topic of Ordinary Saints at Square Halo’s annual conference. In my notes from that address, I wrote the following, which pierced me in a way that leaves me tender still.“If you want to wake up the hidden semantic meaning of words, explore the tension of their polarity to watch the field that is formed around them.”

When I searched for this quote in my notes, I expected it to be longer for the ways it has expanded within and stretched me with it. What was planted as a seed has grown into a fruitful garden, offering rest and shade, a place to tend and be tended. What is more, it has grown from an idea about the semantic meaning of words into a framework for delighting in the ways seemingly unrelated things draw near enough together for their fields of brightness to create especially luminous lines of overlap between them. These are the lines along which I trace my path through the world, following the light, chasing beauty, wooed by wonder.

As a linguist, I am enchanted by words that reach out, pressing against permeable perimeters, finding their way between the bars within which we would confine them. In my decade and a half as a Latin teacher, I encountered, time and time again, my students’ desire to shrink words down to a single meaning, for translation to be as simple as following a formula to reach a word-for-word conclusion. I told them what I tell myself now, when I am tempted to dress the ineffable in what fits me: the goal of translation is to communicate ideas, not words. Or, as my daughter’s Greek professor says, “All translation is interpretation.” The idea to be conveyed will always be greater than the words we find to convey it.

This is the soil into which the seed planted in 2023 put down roots, anchored in rich humus comprised of layered experiences broken down to become knowledge over time. I know in my being that idea-for-idea and word-for-word are not the same, an understanding borne out of failure after failure to communicate what I mean with words that carry meaning beyond my purpose for them. I learned this, whether or not I was ever taught it. The words I borrow bear the capacity of a well. If I lean over the edge, dipping my cup into waters that stretch deeper than I know, I may find myself struggling to keep my head above water, when all I wanted was a sip.

Sometimes, we lean on words as if they are solid blocks with well-defined edges, firm enough to withstand the pressure of stacking arguments, brick upon brick. We compress them into impenetrable walls of meaning, as if the words we arranged were modules of cold, hard fact. But words are flexible units whose meanings are bolstered by their relationship to those around them. Language shapes words through context, using comparison and contrast to clarify ambiguity like the hands of a potter around a lump of clay. There is push and pull as words form an aptly shaped vessel for transferring the idea from one person to another.

If this is the essence of communication, then perhaps we must get a feel for the medium of language before we are able to wield it with any skill. And what better way to get a feel for something than to play with it? In play, we see how it sticks and feel its flow in the repetition of rhythms, practicing pauses or being carried along in the swift current of clever cadence. We explore connections between our concrete senses and abstract emotions, running fingers gently along the boundary that forms where interoception and proprioception meet, tracing the shape of what we mean when we say we are “human.” Wails give way to words, and this becomes the language of childhood.

I don’t know about you, but poetry was my first language. Rhyme and song, meter and verse made up the English through which I first encountered a world beyond my immediate senses. I imagine that might be true for a lot of us; poetry is the language we use with our young ones. Before they have the capacity for rational thought, we speak to them with poetry, calm them with song. We often engage infants with patterns of language that employ exaggerated vocal range and emphasize rhyme and accent, approaching language as a mode of play between adult and pre-verbal child. Think of all the nursery rhymes passed on from grandparent to grandchild, the action rhymes or finger plays that parents use with children to develop gross motor and vestibular systems. Of course, when we sing-song “This is the way the ladies ride” while bouncing a toddler on one knee, or sing “ring around the rosie,” circling around before a planned tumble, we’re likely not focused on the role of the game in child development. We’re just doing what delights, engages, and occupies the child by connecting with them on what seems like their level. But how is it that poetry, song, and dance are so natural to the frame of a young child, when so many adults struggle to enter into poetry, song, and dance themselves? Did we, perhaps, include poetry in the box when we, as Paul says, “gave up childish ways?”

One of the fields of polarity I have been exploring exists in the tension between the childishness of I Corinthians and the childlikeness praised in the gospels. We use these words alongside the assumption that others hear them with the same meaning that we do, that our usage holds the same defining bounds that the ancients had. But what if some of what we eschew in maturity is not child-ish, but child-like? What if the language of childhood, with all of its poesy, offers a semipermeable lens through which the Real can pass, allowing us to see it more clearly?

My childhood memories are filled with rhymes and songs, as far back as I can recall. The first stories I remember are from The Bible-Time Nursery Rhyme Book. It was my favorite, and my dad read it to me until it was tattered and worn, loved to pieces, quite like the velveteen rabbit. Though I don’t recall having a stuffed animal that I carried around, these rhymes went everywhere with me, tucked into my memory, taking up residence in my heart, rehearsed over and over until they became part of how I made sense of the world. Like the velveteen rabbit, they were Real. I played with the sounds and the rhymes, substituting words to fit the context of my current activity. We learn by imitation, and these were my exemplars.

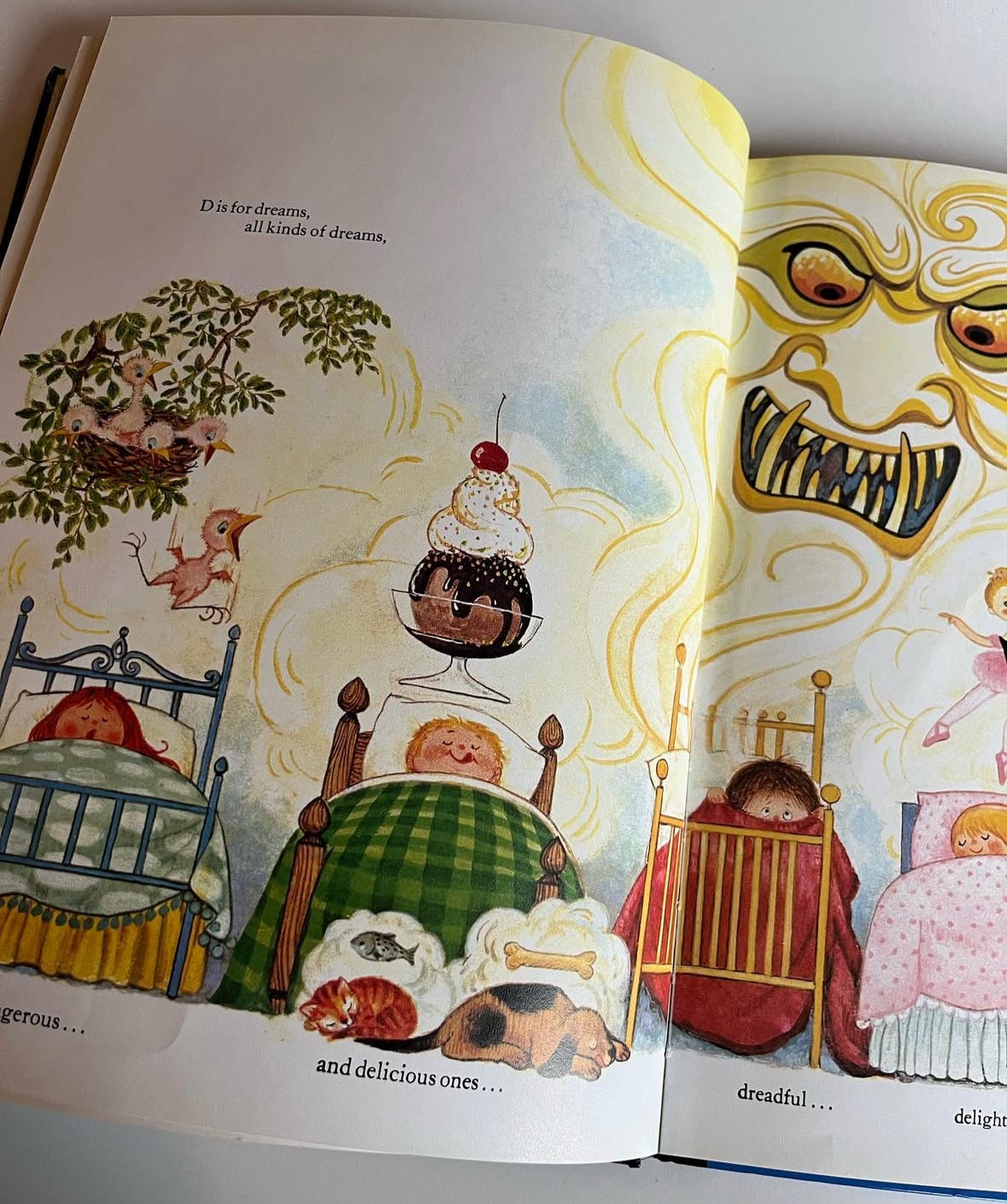

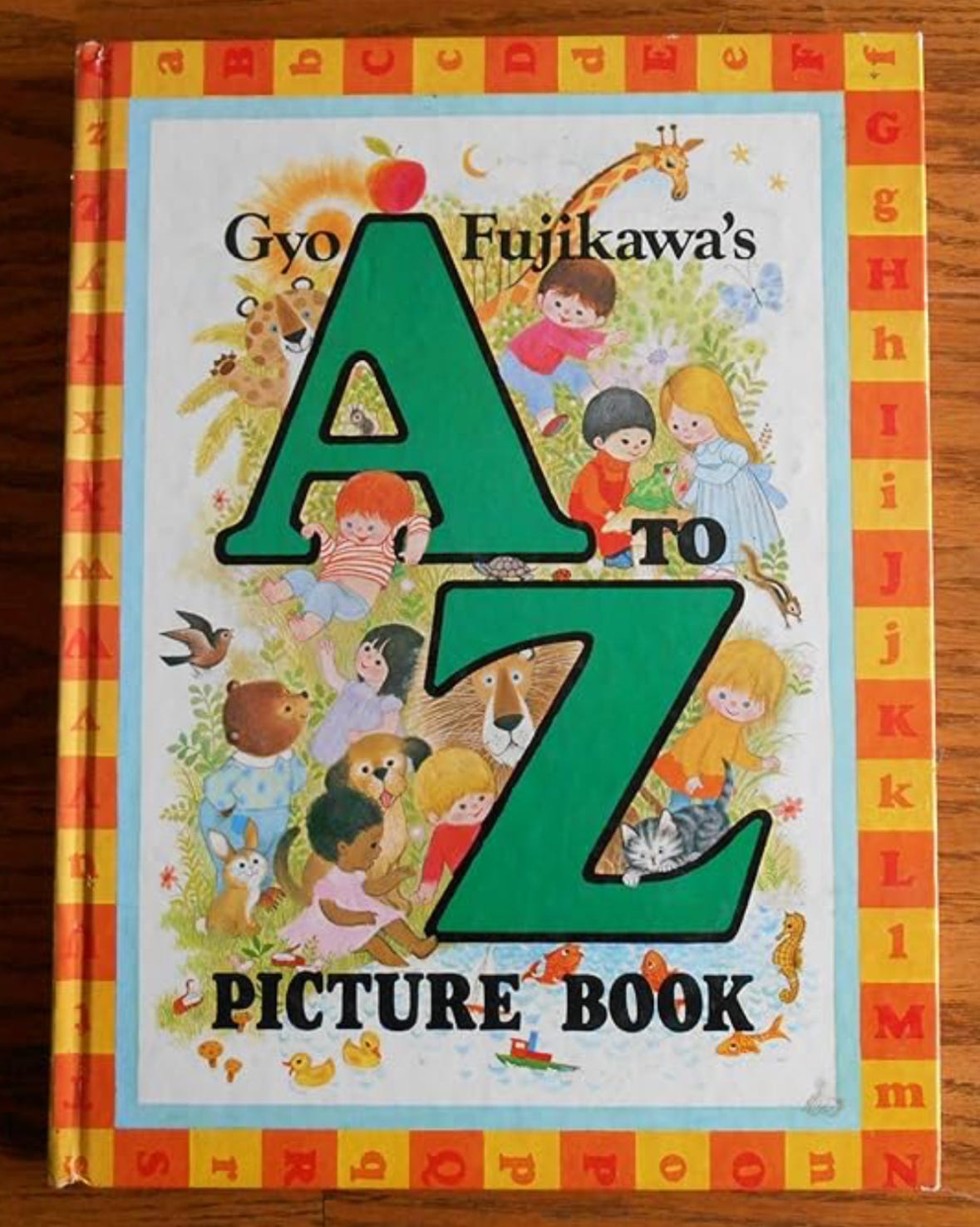

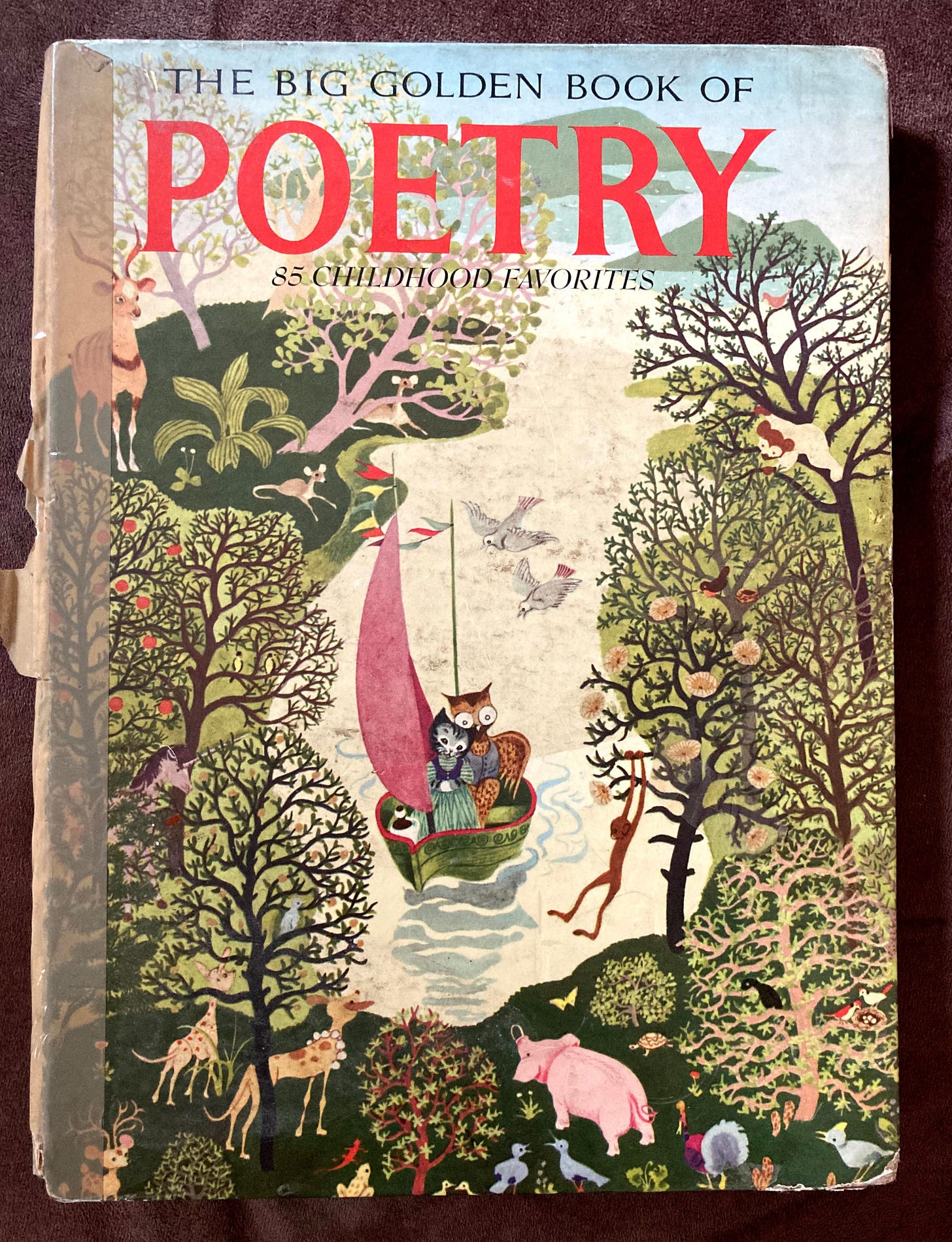

Neither of my parents understand or enjoy poetry as adults, but they made a feast of it for me as what was appropriate to nourish a child, strengthening my imagination in ways that linger today. Gyo Fujikawa’s A to Z Book populated my early imagination with words and images that painted the world as a place of wonder and discovery. Before I knew the words I took in the images, shaped by the emotion they evoked. As I grew a capacity for reading, longer stories and poems were added to the list from books like A Child’s Book of Poems and The Big Golden Book of Poetry, which had been my mom’s. I was particularly drawn to the short poems I could recite within a breath or two.

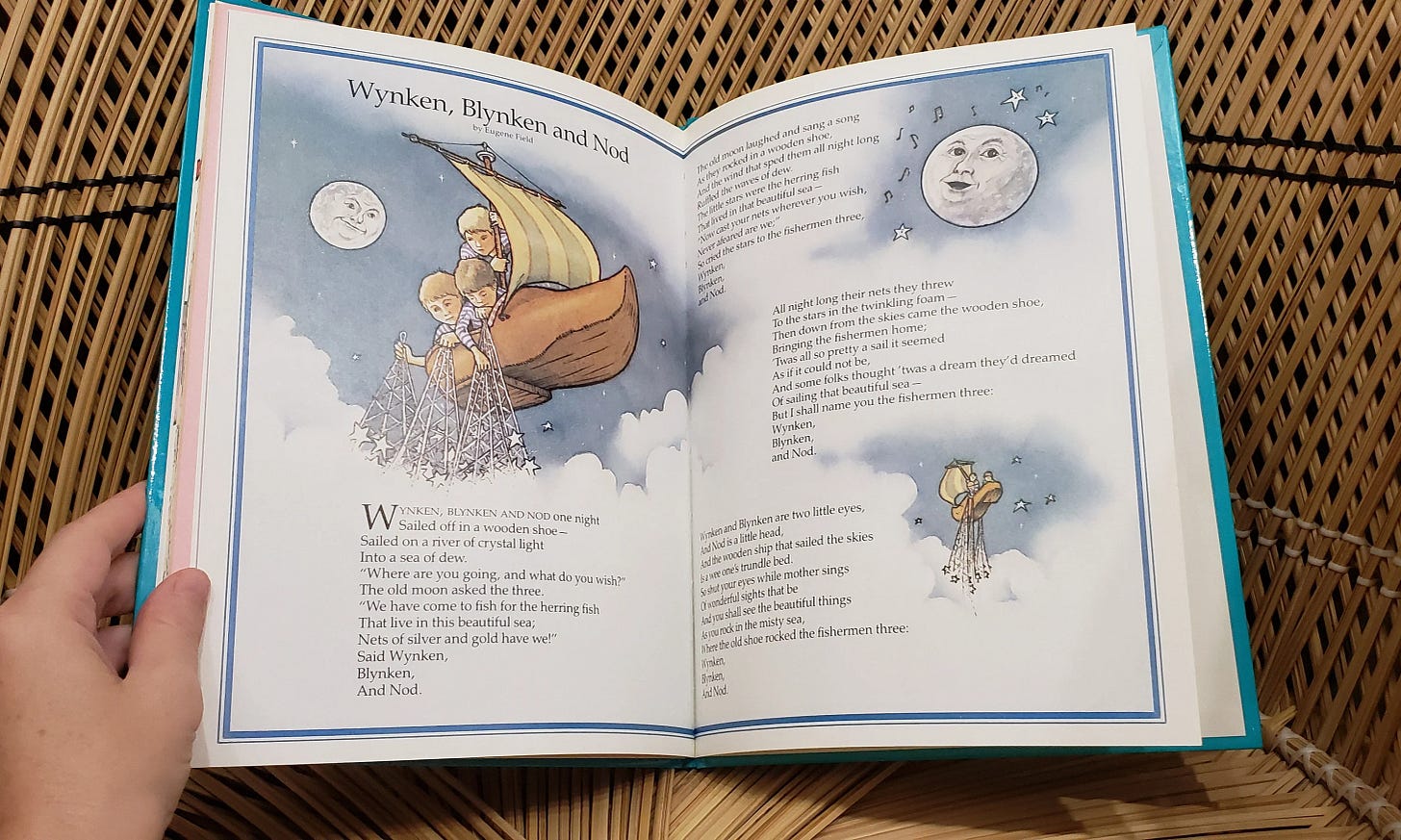

The Care Bears Book of Favorite Bedtime Stories might not look like a classic, but it was full of poems and fairy tales with some lovely illustrations. It became a beloved companion in my grade school years and I read it over and over and over. Like The Bible-Time Nursery Rhyme Book, it too was loved until it became Real. I loved the sound of the words, playing on my tongue in spare moments. I might be on a swing set when the cadence of the swing would match a rhyme and I would delight in its rhythm over and over while the wind rushed past me, whipping my hair back and forth with the momentum of the swing. “The gingham dog” took me forward, “and the calico cat” took me back, “side by side” forward again, “at the table sat” and back… As I went about my days there played on the periphery Wynken, Blynken, and Nod, who sailed off in a wooden shoe, or The Owl and The Pussycat. The accompanying images from the book made sense of the rhymes in my head in a way the words didn’t have to. They were the stuff of daydreams and fairy tales, and I loved them.

In elementary school we had a yearly speech meets for which we memorized and recited poems for judges and an audience. I don’t remember if I performed well, but I remember the poems I learned. Somewhere in the dark depths of my subconscious they reside still, like a beaked whale, surfacing occasionally, but mostly staying out of sight.

I have little memory of learning poems or studying poetry beyond elementary school, even in college as an English major. I’m sure we did, I just don’t remember it. As a result, I didn’t learn to come at poems from the outside until much later. Even then my attempts felt like I was faking it, like there was some secret to poetic analysis I didn’t understand. But what I have known about the world, what I have experienced in it, has made sense through poetry for as long as I can remember. It was the vehicle through which I navigated my emotions, moving from how I felt to making sense of it. It was a bottom up approach, not a top down one; I couldn’t think my way to feeling or understanding what I was going through. I couldn’t tell you about the poetic form or rhyme and meter, but I could feel it and that I could explore.

I think that’s what poetry offers us, even now: not an opportunity for analysis or erudite exploration of an elevated existence, but a place in the circle to sit with the words we borrow from others, rolling them around between us like children at play.

Most of what I know about poetry has come through the practice of it, carving out space with words to process whatever I am experiencing, including the stories I tell myself to make sense of it. For as long as humanity has passed down what it means to be human, generation after generation, we have done so through poetry. Maybe it’s not the language of children, but the language of anyone still learning what it is to be human. If so, then perhaps poetry is for us all.

An Invitation

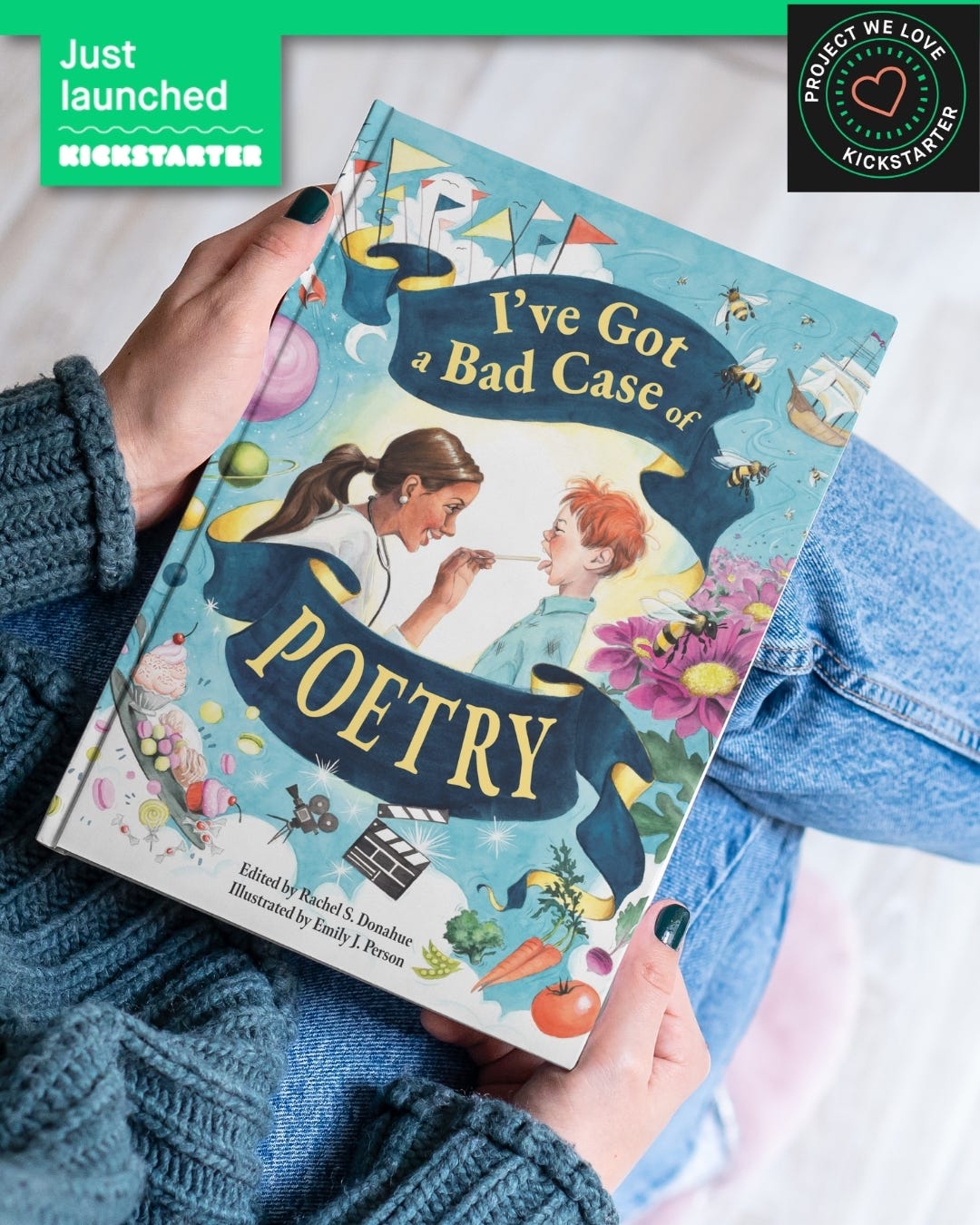

If you’ve made it this far, you know which books shaped my poetic imagination, through both word and image. Bandersnatch Books aims to shape the imaginations of this generation and the next with a brand new illustrated children’s poetry anthology. This hardcover anthology includes the work of 62 poets, who contributed 170 original poems (including 5 of my own), alongside whimsical illustrations by Emily J. Person. It’s made by humans, for humans, and you’re invited to be part of bringing it into the world.

Bandersnatch Books launched the project yesterday on Kickstarter, where you can go to find out more to back the project, reserve your own copy, and help make the world a better place through poetry.

A Poem

It’s not uncommon for me to share a recent poem or two in this space, but today I’m going to share the most un-recent poem I have. Among the moments of my early life recorded by my mom was this little gem from July of 1983. My poet bio says that I have responded to life through poetry for as long as I can remember. As support for that claim, I’ll leave you with this bit of evidence that I’ve been doing so at least since I was three.

TABLE MANNERS

(An original poem by Elizabeth Bitikofer, 3 years old)

May I be excused?

Please say yes today.

You will say "Did you eat it all?"

And then you'll say "You may."

I love this! I read books of Shel Silverstein and Jack Prelutsky poetry over and over and began writing my own poems in middle school. Music was always in me from a young age because my mom sang and so when I started playing guitar I could finally create space to find my own melodies. I relate to making sense of my life through poetry, sometimes a rhyme will lay truth bare in a way prose can’t. I love hearing your thoughts, congrats on having those poems published in the book as well. Praying blessing over the Kickstarter that is such a needed thing!

I fear I will never love poetry the way so many of my friends do. I love certain poems, but it’s not an all-encompassing love. But I do love WORDS and language and playing with them in stories, and your thoughts here about how they grow and push each other to communicate meaning is a powerful thought.